Monarch Life Cycle and Natural History

About the monarch butterfly

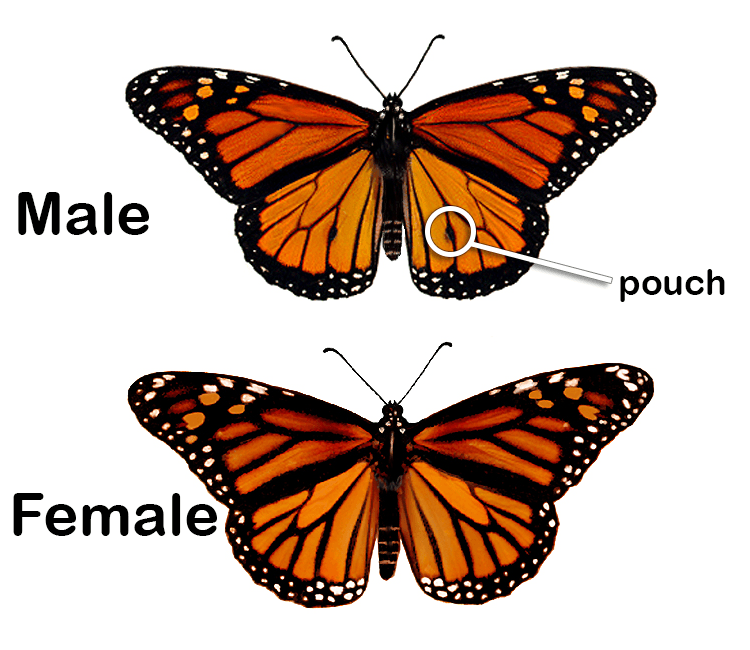

The monarch butterfly is found throughout North America, from Canada south to South America and the Caribbean. They have also spread to southwestern Europe, Australia, and Oceana in the 1800s. The monarch might be the most widely recognized of all American butterflies with its distinct orange, black and white wings. The black border around its wings, rimmed with white spots, makes them look like stained glass windows. When opened, its wings can reach as wide as 4 inches. You can tell the male monarch from the female by the two black spots on his hind wings and the thinner black webbing within. The female’s webbing is thicker and she lacks the distinctive wing spot.

Habitat and diet

Monarchs live mainly in prairies, meadows, grasslands, and roadsides where there are abundant flowers and milkweed plants. As caterpillars, they feed exclusively on milkweed, which makes the monarch toxic to predators such as birds. The monarch’s survival depends on this chemical defense. Adults are generalists and nectar from a variety of blooming plants.

Monarch migration

Adult monarchs are seen flying in Nebraska from June through the fall, so having plants that bloom throughout the summer and fall are needed for the adults to thrive. You can also report monarch sightings to journeynorth.org.

Reproduction

Monarch butterfly reproduction is a complicated process. One female monarch can lay upwards of 400 eggs. The eggs are deposited on the underside of milkweed leaves and will hatch in as little as 3 days, depending on the temperature. The caterpillars, or larvae, feed on milkweed leaves for about 2 weeks, and grow from 2 mm (the thickness of a nickel) to 5 cm (2 in) long and molt (shed) five times. The caterpillars then attach themselves to a twig and shed their skin one last time to transform into a chrysalis, or pupa. This final shedding can happen in only a couple minutes! Packed tightly inside, the caterpillars will undergo the transformation into an adult butterfly in about 2 weeks. The entire life cycle from egg to adult is complete in about a month. In Nebraska, multiple generations of monarchs are born every summer.

Life span and generational migration

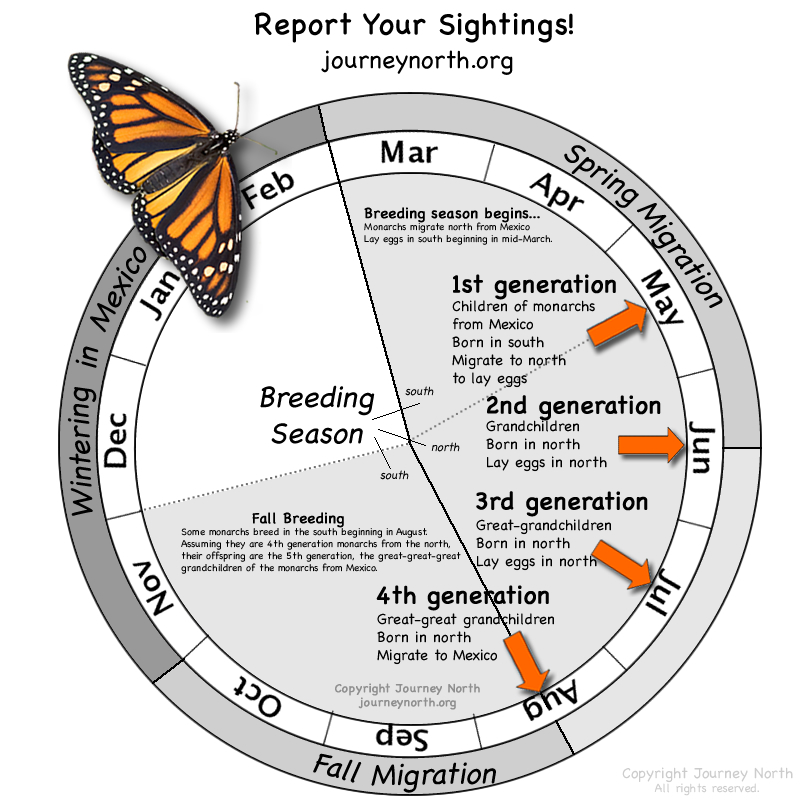

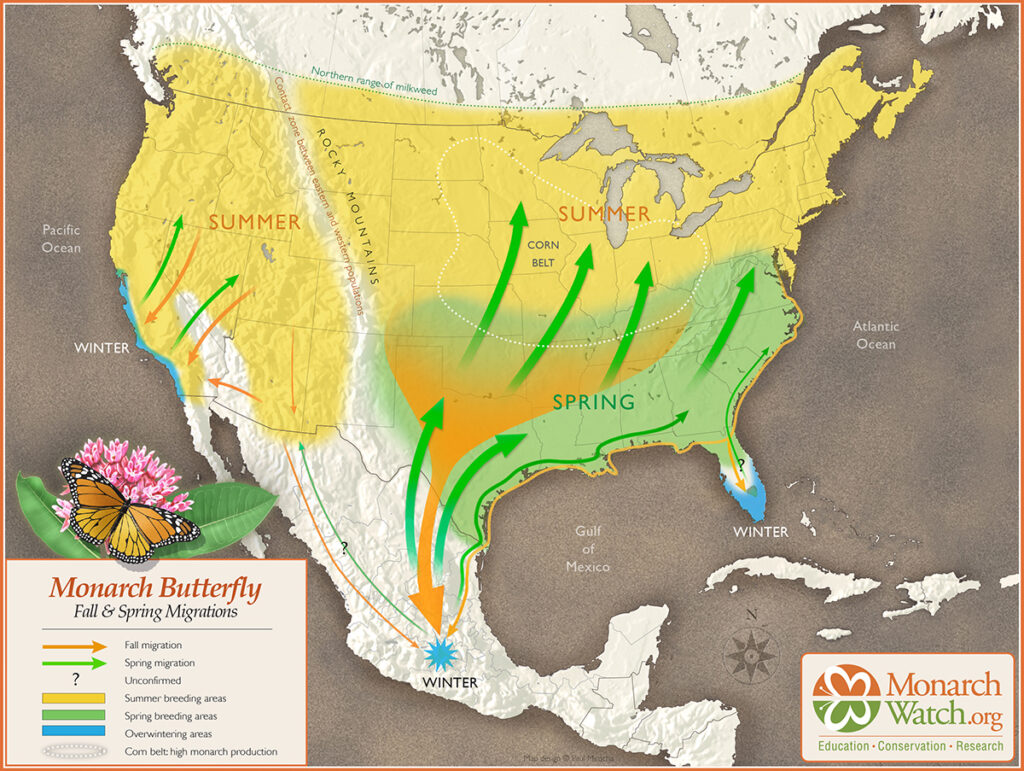

The adult monarch butterfly typically only lives for a few weeks, unless it is lucky enough to be the last generation born in late August. The last generation is the migratory generation and can delay reproduction to live 8-9 months. They migrate south to warmer weather, because monarchs cannot survive Midwest winters. These migratory monarchs must make the journey to their overwintering grounds in central Mexico. For Nebraska monarchs, that means a 1,500 mile one-way trip; but for some Canadian monarchs, it can be over 3,000 miles!

Scientists believe that monarchs use the position of the sun to let them know to begin their migration south. They also believe that the earth’s magnetic field helps them to figure out where to go. Monarchs need a lot of energy to make this trip. They store fat gathered from the nectar of late summer blooming plants, which helps them make the long trip south. In the spring, those that survived the winter move north and lay their eggs in Texas and the southern United States. Each generation continues to move north. Nebraska’s monarchs are likely the second to forth generations each year.

Population status

Unfortunately, the eastern monarch butterfly population (east of the Rocky Mountains) has declined 70–90% in the last 25 years. There are many factors contributing to their decline. Across their breeding grounds, grassland habitat that once had milkweed and blooming flowers throughout the season has been reduced. The use of herbicides and the widespread use of neonicotinoid insecticides are also linked to the decline in monarch numbers. Another major factor contributing to the population decline occurs in the monarch overwintering sites in Mexico where illegal logging in protected areas is eliminating the remaining monarch winter habitat of oyamel fir trees.

The western monarch population (west of the Rocky Mountains) is doing even worse with less than 1% of their population remaining from the 1980s. While the wildfires did not help them in 2020, their biggest threat comes from the loss of overwintering habitat. Many of the trees monarchs have used for years are being harmed by human actions like tree trimming or development.

Many governments in North America have designations about the status of monarchs. In December of 2020, the monarch butterfly was under consideration for protection under the Endangered Species Act. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that listing was “warranted but precluded”. This means that while the monarch meets the criteria to be listed, there are too many other species that need more urgent protection for the monarch to make the list at this time.

The status of monarch butterflies will be reviewed each year until the monarch either is listed or recovered enough to no longer meet listing criteria. An updated decision is set for November of 2023. Additionally, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has designated the monarch as endangered. The Mexican government created the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve which protects 62 square miles of forests in the Sierra Madre Mountains, where hundreds of millions of monarchs spend each winter.

Help monarch butterflies

While there are many factors contributing to the monarch population decline, you can make a difference where you live or work.