Northern redbelly & finescale dace

Status: Threatened

The northern redbelly dace (Chrosomus eos) is a small fish with an olive-brown colored back and two dark bands along its sides. Between the two stripes is an iridescent, silvery band. With the exception of breeding males, its stomach is cream to yellow in color. Breeding males have a bright yellow-orange to red underbelly leading to the common name of the species. The fins of the redbelly are typically white; during breeding season fins are yellow.

The northern redbelly dace is similar to the southern redbelly dace. The northern species has a shorter, more rounded snout. The southern species is not found in Nebraska.

The finescale dace (Chrosomus neogaeus) has a brown-gray back and a dark, thick gold-orange stripe along its side. Between the back and side stripe, there is an iridescent, silvery band. Their fins are clear to yellow. The body is stout with a large mouth.

Both species have tiny, nearly microscopic scales covering the entire body giving them a smooth, almost shiny, appearance.

Both fish range in size from 2-5 inches with the finescale being larger than the redbelly. The males of each species are smaller than the females.

Finescale and redbelly are similar and often inhabit the same streams. Compounding the issues is the fact that northern redbelly and finescale dace often hybridize with offspring retaining characteristics of both species.

The few predators that do exist for both species include sunfish such as bluegill. When predators are present, both dace species will most likely not inhabit the area or will occur in low numbers.

Range

Both dace species are considered to be northern species typically found in colder regions. Their range extends from Halifax, Canada in the east to Alberta, Canada in the west and south to Nebraska. The finescale dace can be found as far north as the Yukon Territory.

The Nebraska population is separated from the northern populations by several hundred miles. It is believed the species expanded their ranges to Nebraska as glaciers advanced south about 12,000 years ago. As glaciers retreated, small pockets of the fish remained in these southern areas.

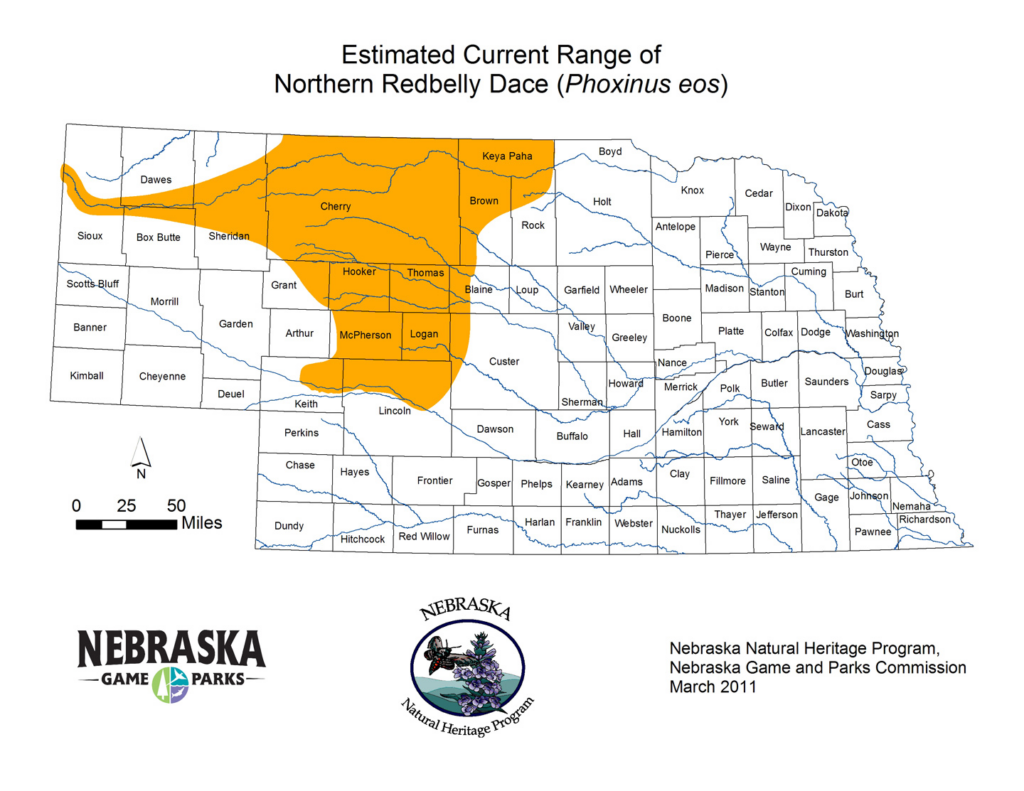

In Nebraska, the finescale dace is found throughout the northern Sandhills and in the Niobrara River west into the Pine Ridge area. Two smaller populations exist in the Platte River near North Platte and Loup River north of Grand Island.

The northern redbelly dace occurs throughout the western half of the Sandhills in Nebraska. It can also be found in the Niobrara River west to the Pine Ridge area.

Habitat

Northern redbelly and finescale dace are both found in small, slow-moving streams. As sight-feeders, they must have clear water. Consequently, they prefer creeks lined with sand or gravel as opposed to mud. They prefer quiet headwaters, small marshes and beaver ponds.

Diet

Northern redbelly dace are planktivores, meaning they eat tiny plants and animals which float in the water column. They also can eat small aquatic animals and large quantities of algae.

Finescale dace primarily eat aquatic invertebrates (small insects and clams). The finescale does not have teeth in its mouth, but rather has large teeth in its throat that aide in crushing and shredding larger insects and other aquatic invertebrates. The finescale may also eat plankton and algae.

Reproduction

Spawning periods are dependent on water temperature. For redbelly dace, spawning occurs from May to August; for the finescale dace spawning occurs from April to June.

Redbelly dace use heavy vegetation for reproduction, typically in the form of filamentous algae. Normally, multiple males will chase a single female into thick vegetation. Here, the female will lay 5-30 eggs; males immediately fertilize the eggs. The female quickly darts to another area of vegetation where she lays a new group of eggs. Eggs of the redbelly dace hatch in 8-10 days and receive no parental care. The young will mature in approximately 2-3 years.

Finescale dace do not use vegetation for reproduction. Rather, numerous adults – both male and female – gather near a covered depression in the sand. When a single pair is ready to mate, they dart into the depression where the female lays 30-40 eggs. The single male fertilizes the eggs. Eggs mature in four days and receive no parental care. Young mature in 1-2 years.

Most eggs and young of either species do not survive into adulthood. Most eggs and larval fish are eaten by predators.

Population status

Although considered a secure species in most of its range, both the finescale and northern redbelly are considered threatened in several states including Nebraska. They were added to the Nebraska threatened species list in 1976; they are not listed as a federal threatened or endangered species.

Management and outlook

Both species are greatly impacted by any changes to the spring-fed streams they inhabit. One of the greatest threats is the depletion of water from these streams through pumping of groundwater. Also contributing to the alteration of stream hydrology is the creation of dams for flood control and irrigation.

Additionally, any increase in water turbidity has a negative effect on these sight-feeding species. When normally clear waters become murky, both species cannot find food. Construction projects, cattle operations, and any practice which increases silt or soil in the streams is highly detrimental.

Both species are also impacted by the introduction of non-native species. These introduced species create pressure through competition, predation, and potential introduction of parasites and diseases.

A local threat for both species is the collection of individuals for bait.

Conservation help

More research is needed to determine habitat, migration, and flow requirements for both species to determine how human actions are affecting them. Proper cattle management and erosion control measures should also be continued or implemented to ensure the streams remain clear. Additionally, proper groundwater management will guarantee streams remain viable for both species.

The practice of introducing species to the finescale and redbelly’s habitat should be stopped, and elimination of existing non-native species should be an active conservation practice. Finally, local anglers should take care not to use either species as bait.

Relics of the past

During the Pleistocene, a succession of ice sheets advanced south from the Arctic, several of which reached as far south as Kansas. The cooler climate that brought the ice sheets allowed many species of northern animals to extend their ranges south into the Plains. When the climate warmed and the ice sheets melted, several fishes stayed behind, living in streams that were fed by cool groundwater. We call these fishes “glacial relicts.” The Northern redbelly dace, the finescale dace and the northern pearl dace are among these relics. These fishes prefer cool, clear, vegetated habitats, and their presence indicates a high-quality stream.

References

Stasiak, R. and G.R. Cunningham. 2006. Finescale Dace (Phoxinusneogaeus): a technical conservation assessment. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Online: www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/finescaledace.pdf

Page, L. and Burr, B. 1991. Freshwater Fishes. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York.

NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available www.natureserve.org/explorer.